Indian artifact treasure trove paved over for Marin County homes.

Archaeologists crushed that tribe declined to protect burial site.

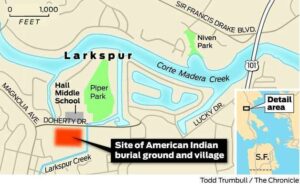

The Rose Lane development in Larkspur was built on top of a large Native American burial ground and village site containing tools, harpoon tips, musical instruments, weapons, the bones of grizzly bears and a rare ceremonial California condor burial.

A treasure trove of Coast Miwok life dating back 4,500 years – older than King Tut’s tomb – was discovered in Marin County and then destroyed to make way for multimillion-dollar homes.

The American Indian burial ground and village site, so rich in history that it was dubbed the “grandfather midden,” was examined and categorized under a shroud of secrecy before construction began.

The site also contained 600 human burials.

No artifacts were saved

All of it, including stone tools and idols apparently created for trade with other tribes, was removed, reburied in an undisclosed location on site and apparently paved over, destroying the geologic record and ending any chance of future study. Not a single artifact was saved.

It was the largest, best-preserved, most ethnologically rich American Indian site found in the Bay Area in at least a century.

“It should have been protected,” said Jelmer Eerkens, a professor of archaeology at UC Davis. “The developers have the right to develop their land, but at least the information contained in the site should have been protected and samples should have been saved so that they could be studied in the future.”

Their work was monitored by the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, who were designated the most likely descendants of Larkspur’s indigenous people.

The American Indian leaders ultimately decided how the findings would be handled, and they defended their decision to remove and rebury the human remains and burial artifacts. “The notion that these cultural artifacts belong to the public is a colonial view.”

Several top archaeologists said a lot more could have been done to protect the shell mound. The problem was that the work was done under a confidentiality agreement.

Archaeologists were stunned.

“In my 40 years as a professional archaeologist, I’ve never heard of an archaeological site quite like this one,” said E. Breck Parkman, the senior archaeologist for the California State Parks. “A ceremonial condor burial, for example, is unheard of in California. This was obviously a very important place during prehistory.”

Greg Sarris, the chairman for the 1,300-member Graton tribe, was far from apologetic about what happened to the archaeological site. It is nobody else’s business, he said, how the tribe chooses to handle the remains and belongings of its ancestors.

Nondisclosure agreements are relatively common when dealing with Indian burials because of the historical problems American Indians have had with looters, grave robbers and vandals, but the archaeologists believe the developer and the tribe were behind the secrecy.

They also question Larkspur planning officials, who could have protected the mound by ordering a redesign or mandating construction of a cap over the site.

“It’s like the fox watching the henhouse,” said Al Schwitalla, an archaeologist He said radiocarbon dating was arbitrarily limited and DNA testing was prohibited, a move that prevented confirmation of a genetic link to Graton Rancheria tribe members.

A draft report was prepared documenting what was found inside the Larkspur mound, but the actual items are lost to science and future study. That includes atlatl throwing sticks, which were used for hunting before the bow and arrow. There were also thousands of shells and the bones of bat rays, waterfowl, deer, sea otters and some 100 grizzly and black bears. Archaeologists say the remains of the condor, a species revered by the Miwok, could be an indication that the birds were kept as pets, possibly for their feathers.

There were also antler tools, flutes, beads, bone awls, hairpins, game pieces and ritualistic stone objects apparently used to trade for obsidian and beads from Napa-area tribes, according to archaeologists.

“There are a lot of things that went wrong here,” Eerkens said. “It’s really a shame.

The complete article

https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Indian-artifact-treasure-trove-paved-over-for-5422603.php

Carbon-datable geologic strata in the soil was destroyed, and ethnographic information about diet, household life, and trade was lost forever.

A sad situation, to our mind.