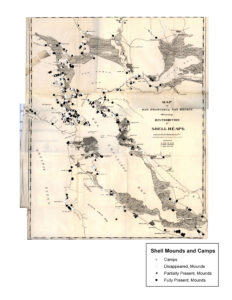

There Were Once More Than 425 Shellmounds in the Bay Area

Four hundred twenty-five is the conservative estimate, made back in 1909 by Nels C. Nelson, at that time a UC Berkeley graduate student. And he did not see them all.

Over the centuries, these ancient earthworks, which frequently contain the remains of Indigenous peoples, have been thoughtlessly plundered and destroyed, falling prey to antiquities collectors, urbanization, and the elements.

Nelson’s map ringing around San Francisco and San Pablo Bays.

The Emeryville Shellmound in 1908. Gone now.

The Emeryville Shellmound turned up a rich variety of material culture: everything from tools and pottery fragments to musical instruments and sea-otter penis bones likely used as awls. A lot of it is stored now at the Phoebe Hearst Museum at UC Berkeley much to the consternation of surviving local Natives.

The West Berkeley Shellmound, one of the richest and most ancient in the Bay Area, is estimated to have been built around 3700 BCE.

In a way, these mounds are time capsules entombing the rich diversity of what we have lost. For anthropologists, they are still-shifting sites of material culture; for the descendants of those buried within, they are living sites of memory and sources of connection. Though they might not seem like living things, these shellmounds are far from inert.

Local Ohlone Indians are currently trying to gain control of the Spengers Parking Lot built on top of the old West Berkeley Shellmound to recreate a sacred site.

The Oyster Point Shellmound at the base of San Bruno Mountain is like walking on a sponge.

This mound at China Camp in San Rafael might not have been on Nelson’s map.

Only a little remains at Point Pinole.

The old Ranger’s Quarters at Sunol Regional Park is built right on top of a mound also called a Midden.